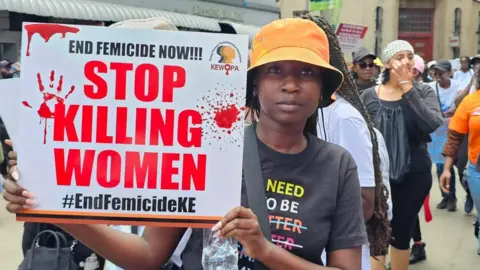

Combat Femicide

Kenya’s recent announcement of Ksh.100 million to combat femicide, as articulated by President William Ruto, reflects a concerning trend in government responses to the escalating crisis of gender-based violence.

The allocation of funds and the launch of the Safe Home, Safe Space campaign, coinciding with the 16 days of activism starting November 25, 2024, seem like positive steps on the surface.

However, the problem lies not in the intention, but in the timing and the scale of the response. The commitment to addressing femicide through reactive measures, rather than proactive and comprehensive reforms.

Thus, will likely fail to curb the rising tide of violence against women. The strategy feels like too little, too late, and here’s why.

A Delayed Reaction to a Longstanding Crisis

President Ruto’s statement that the government is committed to policies to end femicide is commendable, but the unfortunate reality is that femicide has grown into a significant issue in Kenya over the years, with much of the violence well-documented.

In recent months, people have discovered the bodies of women in public places, dump sites and remote areas, often as tragic outcomes of domestic disputes or targeted criminal activity.

In 2024, femicide is not just a Kenyan issue; it’s a global crisis. According to the UN, intimate partners or family members killed approximately 50,000 women worldwide in 2023, and the trend is alarmingly rising in many regions.

Kenya’s efforts seem reactive, rather than preventative, and much of the solution seems to hinge on public campaigns instead of urgent structural reform.

Comparing Presidential Statements with Global Trends

While President Ruto emphasized the need for psychological support, safe spaces, and better education on the signs of abuse, these are not new recommendations.

Countries worldwide, such as Argentina and Spain, have developed extensive femicide laws, comprehensive support systems, and victim-centered approaches that involve systemic reforms, including greater accountability for law enforcement and social services.

In contrast, Kenya’s “Safe Home, Safe Space” campaign feels like an afterthought. The funds allocated Ksh.100 million, are minimal compared to the scale of the problem, especially considering the fact that the Kenya Police Service reported 213 femicide cases in 2023 alone.

By comparison, Kenya’s allocation is a drop in the ocean of need. The failure to provide consistent, sustained funding and comprehensive policy reforms reflects a disjointed, short-term view of a deeply ingrained issue.

Key Indicators of Law Enforcement’s Inadequate Response

Despite President Ruto’s calls for law enforcement to execute its mandate “without delay,” the reality on the ground tells a different story. There are three key indicators that suggest Kenya’s law enforcement is not doing enough to address femicide:

- Lack of Accountability: The president’s directive to enhance gender desks in police stations and hospitals is important, but it’s largely ineffective if there is no accountability for officers who fail to act on reports of abuse. In many cases, police officers meet victims of gender-based violence with indifference or inadequate support. This lack of accountability, and in some instances, victim-blaming, undermines the effectiveness of gender desks and safe spaces.

- Slow Investigations and Impunity: While President Ruto instructed that culprits be held accountable, femicide cases in Kenya often take months or even years to be investigated, with few convictions. The slow pace of justice for victims and their families is partly due to under-resourced police units, corruption, and institutional indifference. A more robust, proactive approach is necessary to address impunity.

- Underreporting and Victim Blaming: A pervasive culture of underreporting remains one of Kenya’s greatest obstacles, with victims either too afraid to report their abusers or discouraged from doing so by social pressures or even police officers. Furthermore, law enforcement officers often downplay the seriousness of femicide, blaming women for their own deaths due to their choices or lifestyle. This cultural issue must be tackled head-on by comprehensive training and a shift in attitudes toward women’s rights and dignity.

Conclusion

The Ksh.100 million allocated to the Safe Home, Safe Space campaign is a welcome but inadequate response to the femicide crisis in Kenya.

While the president’s rhetoric highlights important concerns, the global reality of femicide in 2024, marked by systemic issues of impunity, underreporting, and cultural indifference, demands a far more robust and proactive approach.

Without urgent reforms in law enforcement, greater accountability for perpetrators, and comprehensive policies that address the root causes of gender-based violence, Kenya’s “too little, too late” strategy will not be enough to combat femicide or reverse the rising tide of violence against women.